Feature Blog Article

Alagille Syndrome is an inherited disorder that closely resembles other forms of liver disease seen in infants and young children. However, a group of unusual features affecting other organs distinguishes Alagille Syndrome from the other liver and biliary diseases of infants.

- Alagille Syndrome occurs in about one of every 30,000 live births. The disorder affects both sexes equally and shows no geographical, racial, or ethnic preferences.

- A person with Alagille Syndrome has fewer than the normal number of small bile ducts inside the liver.

What are the symptoms of Alagille Syndrome?

Symptoms of Alagille Syndrome are jaundice; pale, loose stools; and poor growth within the first three months of life. Later, there is persistent jaundice, itching, fatty deposits in the skin, and stunted growth and development during early childhood. The disease often stabilizes between ages four and ten with an improvement in symptoms.

Other features, which help establish the diagnosis, include abnormalities in the kidneys, cardiovascular system, eyes, and spine. Narrowing of the blood vessel connecting the heart to the lungs leads to heart murmurs but rarely causes problems in heart function. The shape of the bones of the spinal column may look like the wings of a butterfly on x-ray, but this shape almost never causes any problems with function of the nerves in the spinal cord.

More than 90% of children with Alagille syndrome have an unusual abnormality of the eyes. An extra, circular line on the surface of the eye can be detected during a specialized eye examination. In addition, some children may have some changes in kidney function.

Many physicians believe that there is a specific facial appearance shared by most of the children with Alagille syndrome that makes them easily recognizable. The features include a prominent, broad forehead; deep-set eyes; a straight nose; and a small pointed chin.

What causes Alagille Syndrome?

Alagille Syndrome is a genetic condition (associated with the Notch signaling pathway and Jagged1 gene) that causes narrowed and malformed bile ducts in the liver. Bile that cannot flow through the deformed ducts builds up in the liver and causes scarring. The scar tissue prevents the liver from working properly to eliminate wastes from the bloodstream.

How is Alagille Syndrome diagnosed?

A diagnosis of Alagille Syndrome usually depends upon finding several different components of the syndrome in an individual. Generally, the syndrome involves five distinct findings, including reduced bile flow, congenital heart disease, bone defects, a thickening of a line on the surface of the eye, and particular facial features. Diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic analysis.

How is Alagille Syndrome treated?

Treatment of Alagille Syndrome focuses on trying to increase the flow of bile from the liver, maintaining the child’s normal growth and development pattern, and correcting any of the nutritional deficiencies that often develop. Because bile flow from the liver to the intestine is slowed in Alagille syndrome patients, medications designed to increase the flow of bile are frequently prescribed.

While reduced bile flow into the intestine leads to poor digestion of dietary fat, a specific type of fat can still be well digested, and therefore infant formulas containing high levels of medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) are usually substituted for conventional formulas. Some infants can grow adequately on breast milk if additional MCT oil is given. There are no other dietary restrictions.

Problems with fat digestion and absorption may lead to deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Deficiencies of these vitamins can be diagnosed by blood tests and can usually be corrected by large oral doses. If the child’s system cannot absorb vitamins given by mouth, vitamin injections into the muscle may be necessary.

Sometimes surgery is necessary during infancy to help establish the diagnosis of Alagille syndrome by direct examination of the bile duct system and through liver biopsy. However, surgical reconstruction of the bile duct system is not recommended because bile can still flow from the liver, and there is presently no procedure that can correct for the loss of the bile ducts within the liver. Occasionally, liver cirrhosis advances to a stage where the liver fails to perform its functions. Liver transplantation is then considered.

Who is at risk for Alagille Syndrome?

Alagille syndrome is generally inherited only from one parent and there is a 50% chance that each child will develop the syndrome. The genetic basis has recently been defined and the “Alagille gene” has been found. Each affected adult or child may have all or only a few of the features of the syndrome. Frequently, a parent, brother, or sister of the affected child will share the facial appearance, heart murmur, or butterfly vertebrae, but have a completely normal liver and bile ducts.

- Have you ever treated any other patients with Alagille before?

- What is the status of my child’s liver?

- Will my child need a liver transplant?

- Will my child need imaging studies done to examine my bile ducts i.e. MRCP?

- If there issues with the ducts, will there be stents placed?

- Should my child see a cardiologist to do testing for my heart?

- Should my child see a neurologist to do testing for my nerves?

- Should my child see a nephrologist to do testing for my kidneys?

- How often should I be following up with you?

- Will my child need to do routine bloodwork (every months, 3 months, 6 months, or year?)

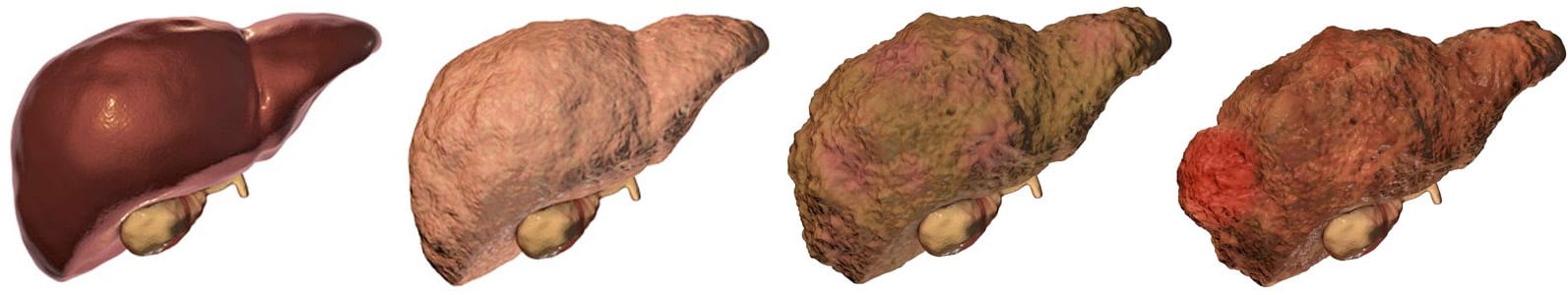

There are many different types of liver disease. But no matter what type you have, the damage to your liver is likely to progress in a similar way.

Whether your liver is infected with a virus, injured by chemicals, or under attack from your own immune system, the basic danger is the same – that your liver will become so damaged that it can no longer work to keep you alive.

Cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure are serious conditions that can threaten your life. Once you have reached these stages of liver disease, your treatment options may be very limited.

That’s why it’s important to catch liver disease early, in the inflammation and fibrosis stages. If you are treated successfully at these stages, your liver may have a chance to heal itself and recover.

Talk to your doctor about liver disease. Find out if you are at risk or if you should undergo any tests or vaccinations.

Clinical trials are research studies that test how well new medical approaches work in people. Before an experimental treatment can be tested on human subjects in a clinical trial, it must have shown benefit in laboratory testing or animal research studies. The most promising treatments are then moved into clinical trials, with the goal of identifying new ways to safely and effectively prevent, screen for, diagnose, or treat a disease.

Speak with your doctor about the ongoing progress and results of these trials to get the most up-to-date information on new treatments. Participating in a clinical trial is a great way to contribute to curing, preventing and treating liver disease and its complications.

Start your search here to find clinical trials that need people like you.

Last Updated on May 13, 2021

Share this page