Feature Blog Article

Galactosemia is an inherited disorder that prevents a person from processing the sugar galactose, which is found in many foods. Galactose also exists as part of another sugar, lactose, found in all dairy products.

Normally when a person consumes a product that contains lactose, the body breaks the lactose down into galactose and glucose. Galactosemia means too much galactose builds up in the blood. This accumulation of galactose can cause serious complications such as an enlarged liver, kidney failure, cataracts in the eyes or brain damage. If untreated, as many as 75% of infants with galactosemia will die.

Duarte galactosemia is a variant of classic galactosemia. Fortunately, the complications associated with classic galactosemia have not been associated with Duarte galactosemia.

There is some disagreement over the need for dietary restriction in the treatment of children with Duarte galactosemia. Consult your healthcare professional for his or her advice on this topic.

- An increased frequency of Galactosemia occurs in individuals of Irish ancestry.

- Classic Galactosemia occurs in 1 in 30,000 to 60,000 newborns.

What are the symptoms of galactosemia?

Galactosemia usually causes no symptoms at birth, but jaundice, diarrhea, and vomiting soon develop and the baby fails to gain weight. Although galactosemic children are started on dietary restrictions at birth, there continues to be a high incidence of long-term complications involving speech and language, fine and gross motor skill delays, and specific learning disabilities. Ovarian failure may occur in girls.

What causes galactosemia?

Classic galactosemia is a rare genetic metabolic disorder. A child born with classic galactosemia inherits a gene for galactosemia from both parents, who are carriers. A child with Duarte galactosemia inherits a gene for classic galactosemia from one parent and a Duarte variant gene from the other parent.

How is galactosemia diagnosed?

Diagnosis for both classic and Duarte galactosemia is made usually within the first week of life by blood test from a heel prick as part of a standard newborn screening.

How is galactosemia treated?

Treatment requires the strict exclusion of lactose/galactose from the diet. A person with galactosemia will never be able to properly digest foods containing galactose. There is no chemical or drug substitute for the missing enzyme at this time. An infant diagnosed with galactosemia will simply be changed to a formula that does not contain galactose. With care and continuing medical advances, most children with galactosemia can now live normal lives.

If my child has been diagnosed, what should I ask my doctor?

Speak to your doctor about your child’s dietary restrictions.

Who is at risk for galactosemia?

The gene defect for Galactosemia is a recessive genetic trait. This faulty gene only emerges when two carriers have children together and pass it to their offspring. For each pregnancy of two such carriers, there is a 25% chance that the child will be born with the disease and a 50% chance that the child will be a carrier for the gene defect.

- Which type of Galactosemia do I have? Type I? Type II? Or Type III?

- What kinds of testing do I need to have?

- Do other members in my family need to be tested?

- What kinds of foods should I be eating?

- Is it possible to be connected to dietitian or someone whom can assist with meal planning?

- Do all my symptoms correspond with galactosemia or is it possible to have other kinds of GI or liver related problems?

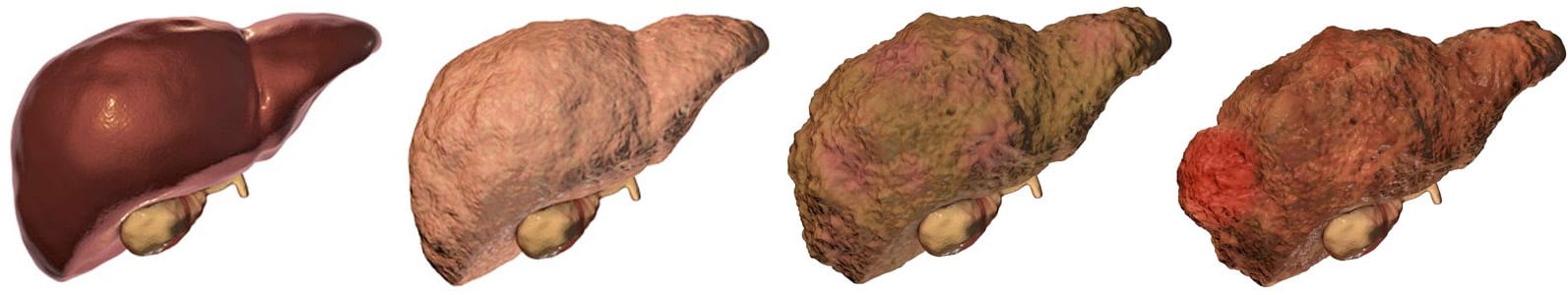

There are many different types of liver disease. But no matter what type you have, the damage to your liver is likely to progress in a similar way.

Whether your liver is infected with a virus, injured by chemicals, or under attack from your own immune system, the basic danger is the same – that your liver will become so damaged that it can no longer work to keep you alive.

Cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure are serious conditions that can threaten your life. Once you have reached these stages of liver disease, your treatment options may be very limited.

That’s why it’s important to catch liver disease early, in the inflammation and fibrosis stages. If you are treated successfully at these stages, your liver may have a chance to heal itself and recover.

Talk to your doctor about liver disease. Find out if you are at risk or if you should undergo any tests or vaccinations.

Clinical trials are research studies that test how well new medical approaches work in people. Before an experimental treatment can be tested on human subjects in a clinical trial, it must have shown benefit in laboratory testing or animal research studies. The most promising treatments are then moved into clinical trials, with the goal of identifying new ways to safely and effectively prevent, screen for, diagnose, or treat a disease.

Speak with your doctor about the ongoing progress and results of these trials to get the most up-to-date information on new treatments. Participating in a clinical trial is a great way to contribute to curing, preventing and treating liver disease and its complications.

Start your search here to find clinical trials that need people like you.

Last Updated on May 13, 2021

Share this page